THE A LEVEL RESULTS FIASCO YET ANOTHER FAILING FOR OUR YOUNG PEOPLE

A Level results day is arguably the most nail-biting moment up to that point in the life of a 17 or 18-year-old. You thought your GCSE results day was terrifying enough but now your uni place, something that could dictate the rest of your career, is dependent on three little letters. The demon that is clearing looms over you as you refresh UCAS track, hoping and praying that your teacher accurately predicted the future. This year, however, the fate of A Level students was mostly out of their control, instead in the hands of an algorithm. The resulting outcry has been unavoidable in the media, whether you know someone who collected their results on Thursday or not. However, with public frustration towards the government’s handling of the pandemic and other issues continuously mounting, were A Level results really all that unfair or is it just another tired case of media sensationalism?

teachers will optimistically predict their students’ grades to help them get their foot in the door for offers

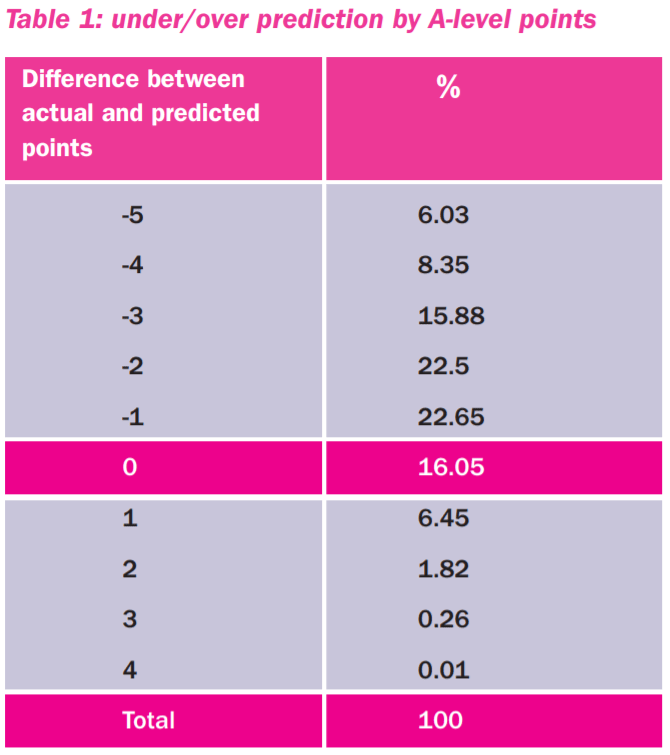

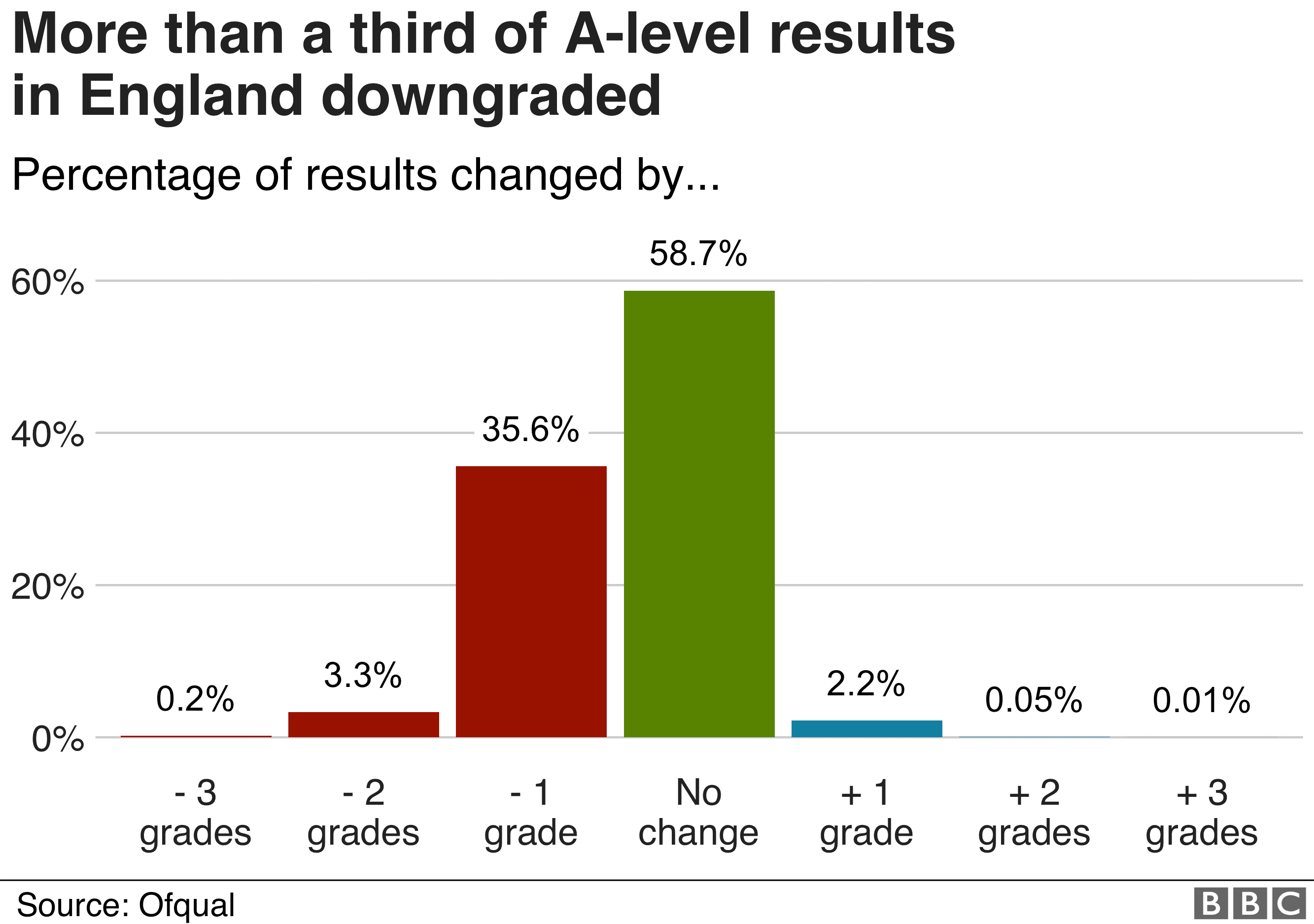

The supposedly shocking statistic that nearly 40% of A Level students’ results were downgraded from their teachers’ predictions is being thrown around in almost every article covering the issue. What we’re not seeing is how this compares to previous years. You know… when there’s no pandemic and students can actually sit their exams. Well first of all it’s important to consider by how much a grade has dropped. A grade that has dropped by one should not be a problem, especially considering that universities and employers know the circumstances students have faced this year and, if they have any sense, should be more lenient. Even in normal times, an A that has dropped to a B will not always cause problems with regards to university places- living proof right here! Why? Well, universities are well aware that teachers will optimistically predict their students’ grades to help them get their foot in the door for offers and thus increase capacity to be able to accept students who don’t quite meet their offers. After the predictions are made, the teacher is absolved of responsibility and it’s the job of the student to get themselves where they want to be. Waning motivation, excessive workload, a difficult exam paper or a bad exam day can all get in the way of this. A report on predicted grade accuracy by University College London (UCL) and the University and College Union (UCU) in 2016 suggests that over 75% of grades fall short of their predictions when students go to take their exams. What’s more, just over 16% of predicted grades are accurate and 8.5% are too low. By how much a grade dropped was also comparatively more favourable for the class of 2020, with the vast majority (35.6% of all grades) of those being downgraded, only dropping one grade whereas typical results are more evenly spread across dropping one, two or three grades. So, in general terms, the algorithm served most students pretty well.

the media’s widespread narrative that A Level students were initially hard done by doesn’t quite hold up.

Obviously, an algorithm isn’t perfect and there is no way computer calculations based on the averages of previous years can suit every individual. However, this is why the so-called ‘triple lock’ system was implemented, whereby students were able to accept their moderated grades, appeal against them with their mock exam results or sit the exams when it is possible to do so. Yes, the government should have anticipated that this system would have had its faults and spent the months they had available to them trying to mitigate these but the media’s widespread narrative that A Level students were initially hard done by doesn’t quite hold up. It’s what happened next that’s really hurt their futures.

In a dramatic U-turn by Gavin Williamson, Secretary of State for Education, just four days after A Level results day, both A Level and GCSE students are to receive the grades initially predicted by their teachers. Welcomed by those wronged by the algorithm, students are now able to accept firm university offers. However, there is still a problem posed by the delay in this response. As is the typically feared outcome of A Level results day, students whose grades are not accepted by their firm or insurance university choices have to scramble their way through clearing. As a result, those who were affected by glitches in the system this year and were quick off the mark will have accepted places in clearing when they now could’ve gone to their firm choice. It is unclear whether students will be able to revert to their firm offer university or if they will simply have to remain victim to the government’s flip-flopping.

The predicted grades in 2013-2015 that represented less than a fifth of actual exam results are now to represent 100% of them.

This U-turn could potentially put students at a greater disadvantage than they realise. Firstly, whilst university capacity has increased to accept as many firm offer students as possible, it has been suggested that they won’t be able to accept everybody, meaning some will have to defer or accept a clearing offer. Additionally, those who do manage to get into their firm choice university may not have actually ended up there, had they taken their exams. The predicted grades in 2013-2015 that represented less than a fifth of actual exam results are now to represent 100% of them. ‘But A Levels were different five years ago- they had AS Levels for all subjects!’ Yes, correct but surely that would mean that teachers actually had more to go on and thus grades calculated by teachers should have been more accurate then? It is unfair on 2020’s A Level students to sugar coat their abilities and have them end up on degree courses that are out of their reach.

It is commonly understood that the algorithm was most detrimental to the least advantaged students. This encompasses a range of categories such as socio-economic factors, type of school and even race. Unfortunately, this is not entirely the fault of the algorithm but a common problem amongst teachers who typically overpredict students from less advantaged backgrounds. Looking again at results from 2013-2015, state-educated, BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) and poorer students are consistently overpredicted more frequently than their counterparts from different socio-economic, educational and racial backgrounds. The reasons for this imbalance is a whole different discussion of its own but it does show that in terms of averages, the algorithm was unfortunately not all that wrong to calculate grades with this in mind. Now is therefore not the moment to put it down to Tory biases against these groups but, in fact, a time to address why this disparity exists in ordinary exam seasons and to figure out a way to close the gap.

None of this is to say that A Level students have been whining over nothing and should have just liked it or lumped it with their algorithm grades. The system should have been properly reviewed before results were released, before students and universities were left in the mess that they now find themselves. Neither the algorithm nor the receipt of predicted grades will serve as appropriate substitutes for actual exam results. Not only will they potentially send this year’s students down the wrong career path but could also devalue the hard work of recent and upcoming A Level students whose grades are likely to appear significantly lower. Ofqual said in July that teachers’ initial predictions would make results 12% higher than last year. A fairer alternative for everyone would have been either some kind of remote assessment for public exams (of course making concessions for students with limited or no internet access) with a safety net grade, like the system adopted at many universities or some way of using predicted grades but flagging them to universities and employers as potentially inflated.