Could a Computer Solve any Problem? A shallow dive into Computability

Computers are often seen as these magical “black boxes” which could seemingly do anything with the help of a skilled programmer. They solve apparently impossible problems everyday and are present almost everywhere in our daily lives. Today I aim to introduce you to the world of Computability and maybe change your perspective on these strange silicon devices. Just a quick warning before you read on, this is going to get a little technical, I have simplified as much as I can and cut out stuff that I’m sure a lot of people will be annoyed about but this is intended for a general audience.

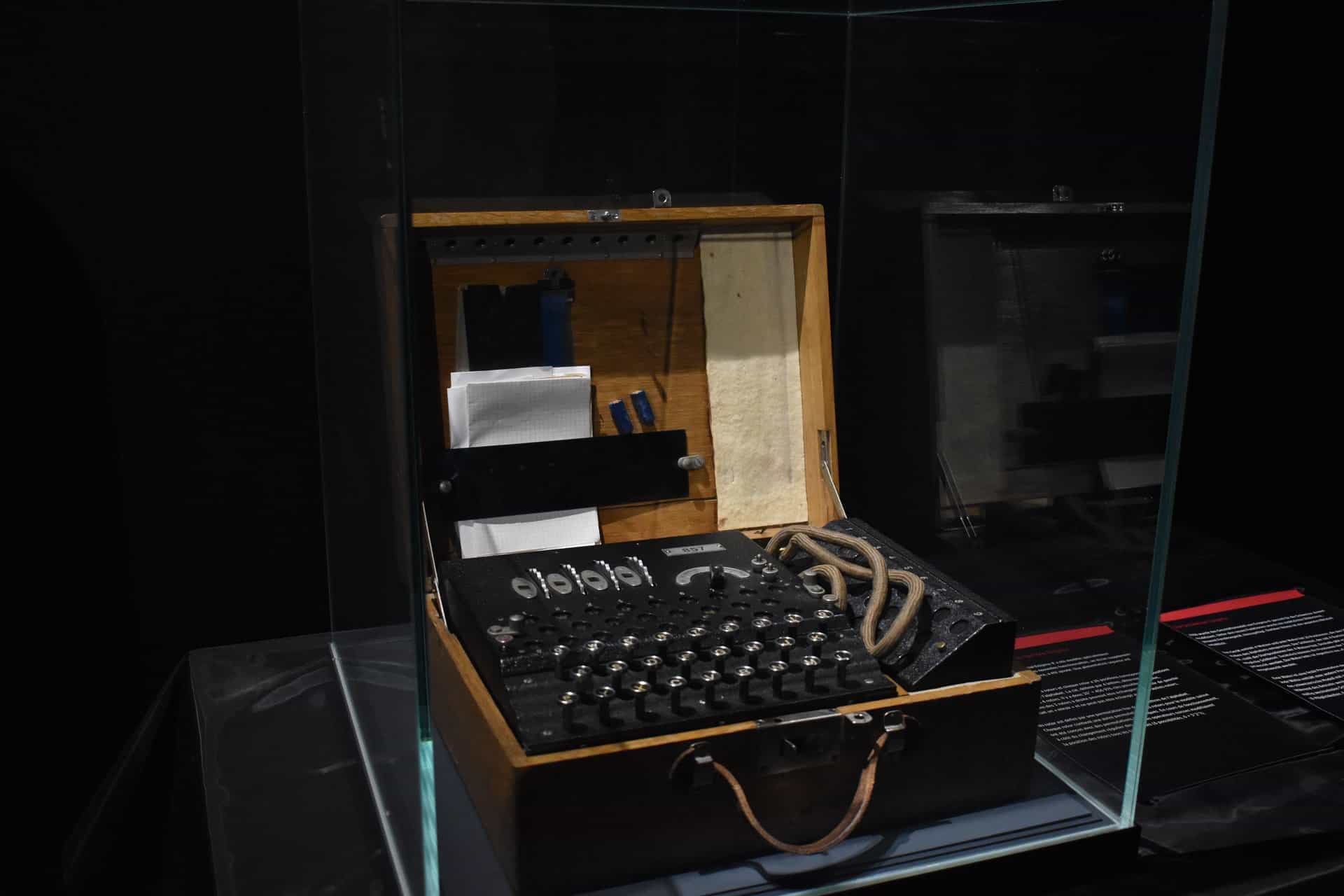

I’m going to start by introducing perhaps the greatest mind in computing, Alan Turing. If you don’t know who he is (and you should) I would strongly recommend reading his Wikipedia page. Alan Turing is responsible for much crucial research within Computer Science, one such example being his model of computation, Turing Machines. A model of computation is something that we can use to reason about computers and computer programs without having to actually build them, they are theoretical tools so to speak. I won’t get into exactly what Turing Machines are or how they work as that’s not important for this article, just know that everything that a Turing Machine can do is something a computer can do. That is to say that there are no programs that you could make on a modern computer that a Turing Machine couldn’t also do. They have what is known as “equal power”.

Alan Turing did a lot of work on the Entscheidungsproblem (decision problem) in the 1930s. This was a problem posed by David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928. The problem is essentially: is there any problem/question that a computer cannot solve? At the time many people, including Hilbert himself, were confident that the answer was no. They thought that given infinite time and infinite memory any problem could be solved.

In order to tackle this problem Turing created his Turing Machines. This was so that he had a basis for reasoning about computation. His approach was as follows, he devised another problem called the Halting Problem, this asked the question: is there a program that can take another program as an input and tell you whether the inputted program halts or not? That is to say, reached an answer. I’m sure you’re all familiar with computer programs freezing on you, this is often due to the program looping over the same piece of code again and again, sort of like a broken record. This is a form of infinite loop, most operating systems nowadays have real time detection for these and promptly restart the program when this happens. Turing was trying to find out if it was possible to discover these types of errors before even running the program.

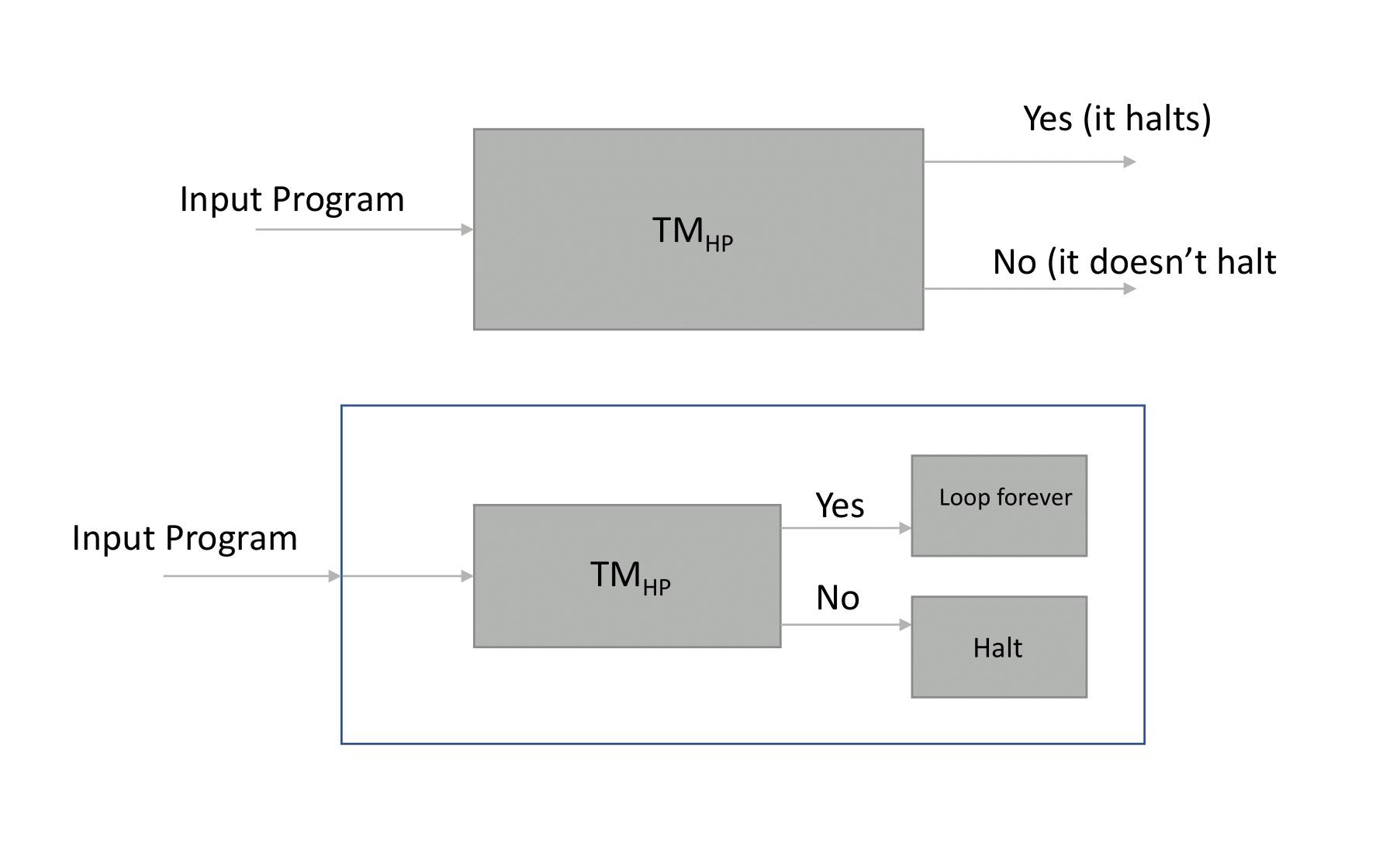

Turing decided to approach this problem backwards. He assumed that such a machine existed, that we could in fact solve the Halting Problem, let’s call this hypothetical machine that solves the Halting Problem: TMHP. This machine takes a program as its input and will output yes or no; it will either say yes (this program will halt) or no (this program will not halt). He then devised another machine that contained TMHP, it would feed its own input into TMHP which would find out if the input program halted or not; if the output to TMHP was yes (the input program would halt) then it would deliberately loop forever, if the answer was no (the input program would loop forever) it would deliberately halt. Then what he did was ask what would happen if you fed that program into itself? What happens now? Well if the program would halt then it would loop, but if it loops it would halt… See where this is going? He essentially said, if TMHP existed then you could create a program that would always do the opposite of what TMHP would predict. Therefore, there is a problem that TMHP cannot solve which means that TMHP cannot solve the Halting Problem for every input program.

If that wasn’t particularly clear, maybe a diagram will clear it up?

The top program is TMHP, it takes an input program and outputs yes or no to whether it halts or not. The bottom program takes the same input, feeds it into the top program and bolts on a program onto each output. When TMHP says the program will halt, it activates another program that loops forever. When TMHP says the program won’t halt, it halts the program.

When you feed the program that makes the bottom machine into the bottom machine you end up with the paradox I stated above. If the machine thinks the program will halt, then it loops forever (doesn’t halt), but if it doesn’t halt then it halts, but if it halts then it loops forever…

Now this is not to say that we couldn’t create a program that could find out if a lot of programs would halt or not. We just cannot create a program that could find out if any program would halt or not. Turing also extrapolated from this that you can prove that a number of other programs are impossible by a method called reduction. Essentially this means that, if you could use another program to solve the Halting Problem, then, it too, must be impossible since the Halting Problem is impossible to solve.

I hope this has given you an interesting insight into the world of Computability and you’ve come away knowing a little more about the mysterious machines that influence our daily lives. As always any questions/feedback are always welcome (see email in the footer :) ). If you found this or any of our other articles interesting feel free to sign up to our mailing list to be alerted of new posts straight to your inbox.